Dividend investing has long appealed to UK investors seeking a balance between income and long-term capital growth. In an environment shaped by shifting interest rates, uneven economic growth, and evolving sector dynamics, dividends can offer a tangible return even when markets feel uncertain. However, not all dividend-paying companies are created equal. A high yield alone is rarely enough. What matters more is whether that income can endure across market cycles.

For UK investors, effective dividend stock analysis hinges on three interconnected ideas: the durability of a company’s cash flows, the sustainability of its dividend yield, and an awareness of how sector rotation influences income reliability over time. Approaching dividends through this broader analytical lens helps transform income investing from a yield chase into a disciplined, risk-aware strategy.

Cash Flow Durability: The Foundation of Reliable Dividends

At the core of every sustainable dividend is cash flow. Accounting profits can fluctuate due to non-cash charges, asset revaluations, or one-off events, but dividends are paid from actual cash generated by the business. For UK investors analysing dividend stocks, free cash flow is therefore a more meaningful metric than earnings alone.

Durable cash flow typically comes from companies with stable demand, strong pricing power, or long-term contracts. Utilities, consumer staples, and certain infrastructure-related businesses often display these traits, though durability can also be found in well-managed firms in cyclical sectors.

Key questions to consider include whether operating cash flow consistently exceeds capital expenditure and whether the business can maintain this surplus during economic slowdowns. Reviewing several years of cash flow statements can reveal how a company performed through different conditions, including periods of inflationary pressure or weak consumer demand.

Balance sheet strength also plays a role. Companies burdened by high debt may be forced to divert cash away from dividends to service interest payments, particularly when borrowing costs rise. A conservative capital structure enhances the likelihood that dividends will remain intact when conditions become less favourable.

Yield Sustainability Versus Yield Attraction

Dividend yield is often the first figure investors notice, but it can be misleading when viewed in isolation. An unusually high yield may signal elevated risk rather than opportunity, especially if it reflects a falling share price driven by underlying business challenges.

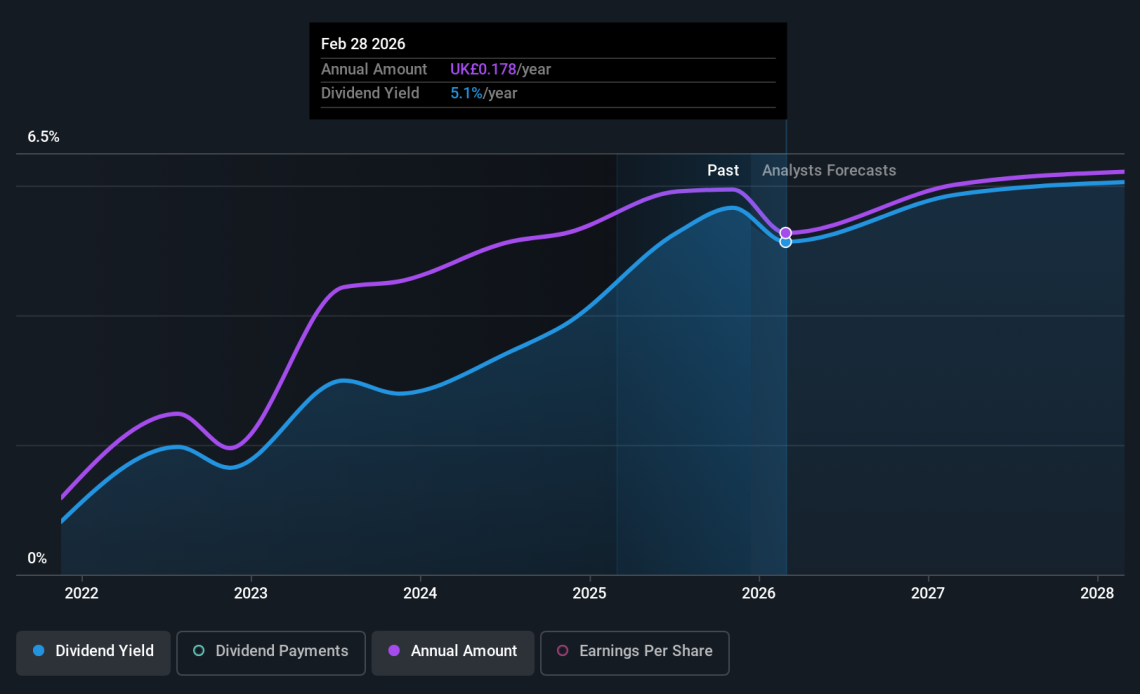

Yield sustainability depends on the relationship between dividends, earnings, and cash flow. The payout ratio, which measures the proportion of profits paid out as dividends, offers useful context. A payout ratio that is consistently too high may limit a company’s ability to reinvest in growth or absorb unexpected shocks.

In the UK market, sustainable dividend payers often strike a balance between rewarding shareholders and retaining enough capital to remain competitive. This balance becomes especially important in sectors facing structural change, such as traditional retail or energy.

Dividend growth history also provides insight. Companies that have maintained or gradually increased dividends over many years tend to prioritise capital discipline and shareholder communication. While past performance is not a guarantee, a stable dividend policy can indicate management confidence in future cash generation.

Sector Rotation and Its Impact on Dividend Strategies

Sector rotation refers to the tendency for different industries to outperform at various stages of the economic cycle. For dividend-focused investors, understanding this rotation is crucial because sector dynamics influence both cash flow stability and dividend reliability.

Defensive sectors such as healthcare, utilities, and consumer staples often perform relatively well during economic slowdowns, supporting consistent dividend payments. In contrast, cyclical sectors like financials, industrials, and materials may offer higher yields during expansionary periods but face greater pressure when growth slows.

UK investors also need to consider domestic and global influences. Financials, for example, play a significant role in UK equity income, but bank dividends can be sensitive to regulatory changes and interest rate shifts. Energy and mining companies may deliver attractive income during commodity upcycles, yet their dividends are often linked to volatile external factors.

A thoughtful dividend strategy does not require perfect timing of sector rotation. Instead, it involves diversification across sectors with different economic sensitivities, reducing reliance on any single income source.

Dividend Analysis in a Changing Macro Environment

Macroeconomic conditions shape dividend outcomes more than many investors expect. Inflation, interest rates, and currency movements all influence corporate profitability and cash allocation decisions.

Rising interest rates can make fixed-income assets more competitive, placing pressure on equity valuations, particularly for income-oriented stocks. At the same time, higher rates can benefit certain sectors, such as banks, by improving net interest margins. For dividend investors, this reinforces the need to reassess sector exposure as conditions evolve.

Inflation presents a more complex challenge. Companies with strong pricing power may protect margins and sustain dividends, while others face rising costs that erode cash flow. Analysing how firms manage input costs and pass them on to customers can provide clues about future dividend resilience.

Conclusion

Dividend investing remains a relevant and potentially rewarding approach for UK investors, but success depends on depth of analysis rather than surface-level metrics. Cash flow durability underpins reliable payouts, yield sustainability guards against unpleasant surprises, and sector rotation awareness helps manage economic risk.

By combining these elements into a cohesive analytical process, investors can approach dividend stocks with greater confidence and clarity. In doing so, dividends become not just a source of income, but a disciplined component of a resilient long-term investment strategy—one built to endure across cycles rather than chase fleeting yields.